Connecting Dots 23 ◎⁃◎ The Innovator’s Inner World

The Innovator’s Inner World

Understanding the mindset of innovation leaders.

Hello,

Welcome to Connecting Dots, a monthly newsletter that explores the space between innovation and leadership. If new you can subscribe here.

In this second article in a series unpacking my research that mapped the experience of innovation leadership, I will outline what innovation leadership looks like through the eyes of our protagonist; the innovation leader. Then I’ll introduce you to the first of the Innovation Leadership Map (ILM) experience scales; Identity.

Stay curious and courageous friends,

~ Brett

PS. I will shortly announce April dates for webinar previews of a new talk called The Quest, An Innovation Leader’s Mindset. Stay tuned for the email or just reply to this one with “Yes please.”

The Innovator’s Inner World

Innovation stirs strong emotions. Not just when doing the work but especially when getting started. Maybe you’ve felt how deeply emotive innovation can be. This truth quickly became evident to me when interviewing seasoned innovation leaders. It was a relief to learn I wasn’t alone.

Unfortunately, we overlook the individual experiences of the millions of leaders who take up the call to lead innovation in their organizations. The experience of leading innovation is simply not understood. It is a desert of knowledge. It turns out this blindspot of lived experiences and practices afflicts all leadership scholarship. By scholarship, I mean the documented evidence, theory and practices of leadership in general. While the literature agrees that leadership is the act of driving change in a group towards a goal, there is little documentation of the lived experience and practices.

What are we afraid of? We can’t develop innovation leadership performance if we don’t know what the experience is in the first place. Why do we stop at all the excellent yet sterile analysis of innovation as though we’re merely moving resources like Lego blocks? Where’s the real work and world of innovation? The peer-to-peer discussions, the risk-taking, activating of ambition, accepting real-world events, creative collaboration, resilience, courage and problem-solving.

When you get into it, leading innovation looks less like a process and more like a phenomenon. That is because it is a phenomenon. One that can be hard to define. In fact, it was only in 2019 that the OECD was able to convene and facilitate 175 global innovation experts to agree on a singular definition.

“An innovation is a new or improved product or process (or combination thereof) that differs significantly from the unit’s previous products or processes and that has been made available to potential users (product) or bought into use by the unit (process). (OECD, 2019, p. 20)

A bit wordy. Though clear. I prefer to just define innovation as “applied invention.” Regardless, it’s wonderful that after 30+ years of concerted efforts they finally landed on a common definition for this beautiful human phenomenon.

That said, I’m not interested in definitions. I am interested in how repeat innovation leaders perform when leading a group to do something new for the first time. This is what the Innovation Leadership Map shows us. It is a synthesis of the emotional, cognitive and behavioural experiences of a leader. Someone who is on the ground leading innovation in the here and now.

Unlike an inventor who is focused on a technical task, innovation leadership is a multi-part task. The leader’s primary role is to negotiate complexity, uncertainty and paradoxical choices to drive a group of people to do something new for the first time. No one person can deliver innovation alone, yet every party can frustrate its progress. It is emergent and can be derailed by small unpredictable events. Each event triggers strong emotional responses in people that the leader must work with.

Digging down we can see the layers of complexity an innovation leader faces:

Strategic complexity

Informational complexity

Procedural complexity

Social/emotional complexity

Navigating this complexity is the real role of the innovation leader. There is much outside the leader’s authority, control and influence regardless of the process or domain of innovation. Because leadership is driving change, each layer of complexity activates disequilibrium as change occurs. In practice, this looks like anxieties, defensive positions and emotional outbursts. All influenced but not controlled by the innovation leader.

The inner context (aka the inner world) is the one thing that an innovation leader can control, or at least learn to control. Tragically, in my research, many innovation leaders didn’t see the personal toll of working through the disequilibrium. Operating with blinders on is a great risk because it’s a fine line between activating, containing and working with these emotional surges productively or becoming consumed by them.

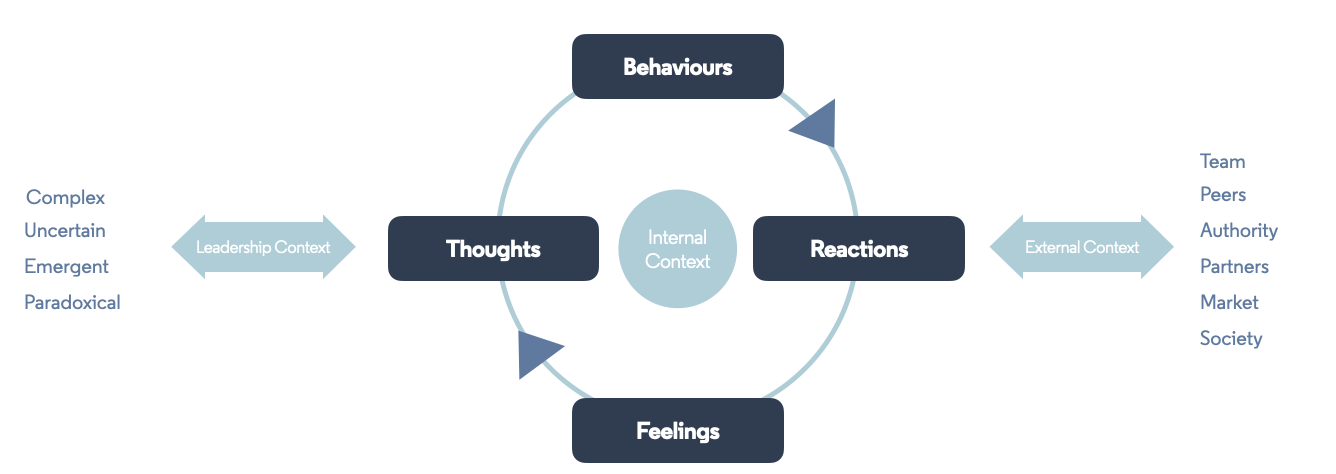

Here is a visualization of what the innovation leadership situation looks like.

A Leader’s Inner World, Brett Macfarlane (2021)

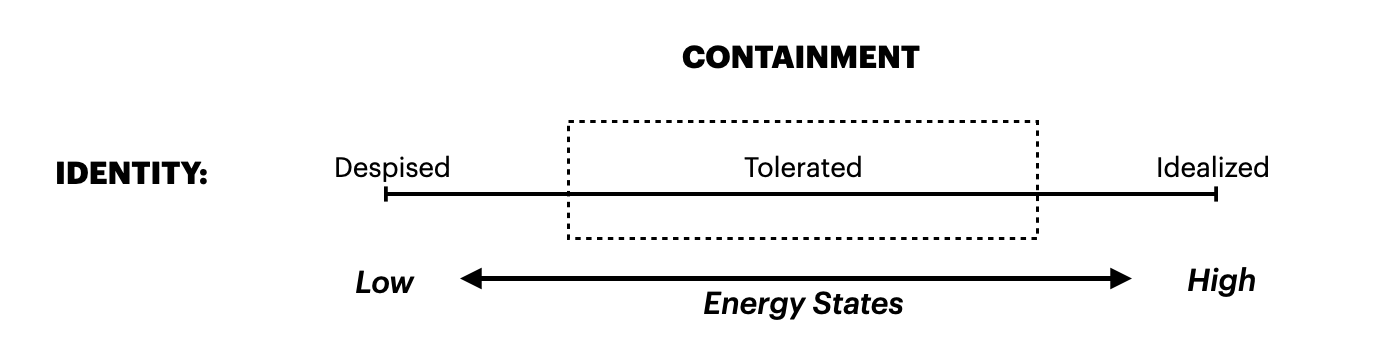

The internal context is what the ILM illuminates. As an example, one of the six experience scales is identity. The identity of an innovation leader is how others see you and how you see yourself at a given moment. Both the identity of you the person in the role and the identity of the role itself. Often the informal role of an innovation leader is a container for all sorts of hope and disappointment regardless of whom currently is carrying the role. “You’ll be hated” was the way one leader described the identity of an innovation leader and why she actively avoids identifying as an innovation leader or innovator.

The experience of leading innovation can be understood through energy states. An absence of energy and progress is insufficient to drive the change innovation requires. Too much energy and the system moves into fantastical or delusion states. Innovation leaders succeed when they can trigger or activate sufficient energy for change and progress yet contain its surges to the extreme ends.

You may have quickly connected the dots that the leader’s performance starts with their ability to contain the energy within their inner world. Only through their self-management can they lead the wider group over time.

What can now serve as an early warning system is if innovation leaders are feeling and seeing evidence of being idealized or despised. Idealization brings about fantastical expectations and a dependency on you for having magical solutions. A position that often follows grand launches, unrealistic timelines or hyperbolic press releases. Alternatively, leaders can find themselves despised and rejected like an unwanted organ transplant. They hole up in a physically or perceptively distant operation.

In between these two low and high energy extremes is the balanced tolerated position. Here there is sufficient energy to drive change (and therefore disequilibrium.) People will tolerate their presence and engage with them. Thus if the identity of being an innovation leader is tolerated in an organization those who may consider you a threat feel it is a manageable or tolerable threat. It is in their interests to work with you and they feel sufficient control and safety to stay engaged.

In other words, the leader is able to contain the emotional experience and maintain a developmental state of cognitive processing as explored in Connecting Dots 22. If they all into the desired or idealized positions they risk losing containment and regress into delusional pessimism. What this introduction to the ILM experience scales establishes is that there is a golden space where effective performance occurs. Next month I’ll explore the identity scale in greater depth, along with how it links more deeply to cognitive processing.

~If this newsletter triggers any of your own experiences, observations or thoughts please do reply. Feedback welcome.

~Also, it’s very appreciated when you forward these newsletters to your colleagues. There is a lot we can learn from each other.

-

TOP IMAGE: Looking up to the Aguille du Midi high above Chamonix, France January 2010.